Ressources

Explorez une large gamme de ressources sur le GCED afin d’approfondir votre compréhension et de renforcer vos activités de recherche, de plaidoyer, d’enseignement et d’apprentissage.

20 résultats trouvés

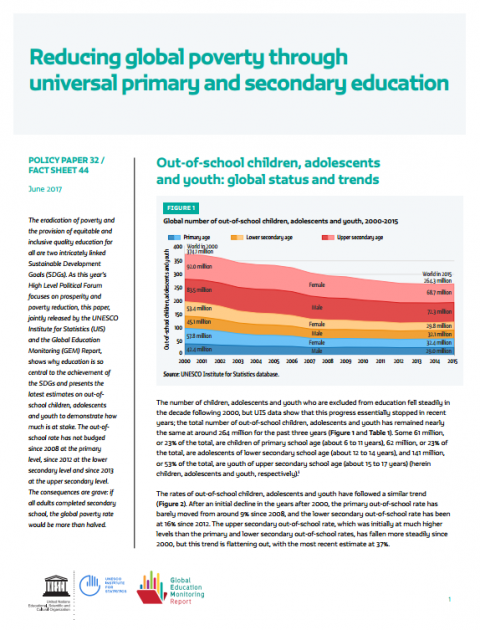

Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education Année de publication: 2017 Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO The eradication of poverty and the provision of equitable and inclusive quality education for all are two intricately linked Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As this year’s High Level Political Forum focuses on prosperity and poverty reduction, this paper, jointly released by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report, shows why education is so central to the achievement of the SDGs and presents the latest estimates on out-ofschool children, adolescents and youth to demonstrate how much is at stake. The out-ofschool rate has not budged since 2008 at the primary level, since 2012 at the lower secondary level and since 2013 at the upper secondary level. The consequences are grave: if all adults completed secondary school, the global poverty rate would be more than halved.

Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education Année de publication: 2017 Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO The eradication of poverty and the provision of equitable and inclusive quality education for all are two intricately linked Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As this year’s High Level Political Forum focuses on prosperity and poverty reduction, this paper, jointly released by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report, shows why education is so central to the achievement of the SDGs and presents the latest estimates on out-ofschool children, adolescents and youth to demonstrate how much is at stake. The out-ofschool rate has not budged since 2008 at the primary level, since 2012 at the lower secondary level and since 2013 at the upper secondary level. The consequences are grave: if all adults completed secondary school, the global poverty rate would be more than halved.  Countering Holocaust Denial and Distortion through Education: Lesson Activities for Secondary Education Année de publication: 2025 Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO Adaptable lessons to foster critical thinking, empathy and tolerance Holocaust denial rejects historical facts outright, while distortion manipulates the narrative. Both phenomena undermine historical truth, fuel antisemitism, and attack democratic values. By addressing these issues, this set of lesson activities for secondary education seeks to build students’ resilience against falsehoods through fostering critical thinking, empathy, and global citizenship. It was developed by UNESCO and funded by the European Commission to equip educators with tools to confront the dangerous spread of Holocaust denial and distortion. With 12 engaging lessons, students aged 14 to 18 will explore the historical facts of the Holocaust while learning to critically evaluate misinformation in today’s digital world. From analyzing survivor testimonies to deconstructing harmful memes and conspiracy theories, this resource features 12 adaptable lessons that focus on historical literacy, media analysis, and social-emotional competencies. Topics range from identifying denial and distortion, evaluating media and online sources, analyzing primary evidence like survivor testimonies, and understanding the misuse of Holocaust history in memes and conspiracy theories. Activities are scaffolded with questions, examples, and practical exercises to encourage analytical skills and promote meaningful classroom discussions. The lessons also include suggestions for incorporating primary sources, visiting memorial sites, and addressing broader issues of genocide and hate. In doing so, the guide aims to not only preserve Holocaust memory but also strengthen the values of truth, empathy, and tolerance in younger generations.

Countering Holocaust Denial and Distortion through Education: Lesson Activities for Secondary Education Année de publication: 2025 Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO Adaptable lessons to foster critical thinking, empathy and tolerance Holocaust denial rejects historical facts outright, while distortion manipulates the narrative. Both phenomena undermine historical truth, fuel antisemitism, and attack democratic values. By addressing these issues, this set of lesson activities for secondary education seeks to build students’ resilience against falsehoods through fostering critical thinking, empathy, and global citizenship. It was developed by UNESCO and funded by the European Commission to equip educators with tools to confront the dangerous spread of Holocaust denial and distortion. With 12 engaging lessons, students aged 14 to 18 will explore the historical facts of the Holocaust while learning to critically evaluate misinformation in today’s digital world. From analyzing survivor testimonies to deconstructing harmful memes and conspiracy theories, this resource features 12 adaptable lessons that focus on historical literacy, media analysis, and social-emotional competencies. Topics range from identifying denial and distortion, evaluating media and online sources, analyzing primary evidence like survivor testimonies, and understanding the misuse of Holocaust history in memes and conspiracy theories. Activities are scaffolded with questions, examples, and practical exercises to encourage analytical skills and promote meaningful classroom discussions. The lessons also include suggestions for incorporating primary sources, visiting memorial sites, and addressing broader issues of genocide and hate. In doing so, the guide aims to not only preserve Holocaust memory but also strengthen the values of truth, empathy, and tolerance in younger generations.  VII Days of Educational Corperation with Iberian America on Special Education and Educational Inclusion: Secondary Education Année de publication: 2011 Auteur: Daniela Eroles Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO Santiago | Spain. Ministry of Education The publication that we deliver contains some of the main papers and reflections emanating from the VII Conference on Educational Cooperation with Ibero-America on Special Education and Educational Inclusion, organized by the Ministry of Education of Spain and the Regional Office of Education for Latin America and the Caribbean ( OREALC / UNESCO Santiago). This publication has the inclusion in secondary education as a central theme, since it was the axis of the VII Conference. It is a particularly critical issue in our region since it establishes the minimum level necessary to escape poverty, to access decent employment and to exercise citizenship. However, access to secondary education is still very low in some countries and is especially low in the case of the most vulnerable populations, being those who most require access to this level of studies to overcome their situation of inequality.

VII Days of Educational Corperation with Iberian America on Special Education and Educational Inclusion: Secondary Education Année de publication: 2011 Auteur: Daniela Eroles Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO Santiago | Spain. Ministry of Education The publication that we deliver contains some of the main papers and reflections emanating from the VII Conference on Educational Cooperation with Ibero-America on Special Education and Educational Inclusion, organized by the Ministry of Education of Spain and the Regional Office of Education for Latin America and the Caribbean ( OREALC / UNESCO Santiago). This publication has the inclusion in secondary education as a central theme, since it was the axis of the VII Conference. It is a particularly critical issue in our region since it establishes the minimum level necessary to escape poverty, to access decent employment and to exercise citizenship. However, access to secondary education is still very low in some countries and is especially low in the case of the most vulnerable populations, being those who most require access to this level of studies to overcome their situation of inequality.  VII Jornadas de Cooperación Educativa con Iberoamérica sobre Educación Especial e Inclusión Educativa: Educación Secundaria Année de publication: 2011 Auteur: Daniela Eroles Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO Santiago | Spain. Ministry of Education La publicación que entregamos contiene algunas de las principales ponencias y reflexiones emanadas de las VII Jornadas de Cooperación Educativa con Iberoamérica sobre Educación Especial e Inclusión Educativa, organizadas por el Ministerio de Educación de España y la Oficina Regional de Educación para América Latina y el Caribe (OREAL C/UNESCO Santiago). Esta publicación tiene a la inclusión en la educación secundaria como tema central, pues constituyó el eje de las VII Jornadas. Es un tema especialmente crítico en nuestra región ya que establece el nivel mínimo necesario para salir de la pobreza, para acceder a un empleo digno y para ejercer la ciudadanía. Sin embargo, el acceso a la educación secundaria todavía es muy bajo en algunos países y es especialmente bajo en el caso de las poblaciones en situación de mayor vulnerabilidad, siendo quienes más requieren acceder a este nivel de estudios para superar su situación de desigualdad.

VII Jornadas de Cooperación Educativa con Iberoamérica sobre Educación Especial e Inclusión Educativa: Educación Secundaria Année de publication: 2011 Auteur: Daniela Eroles Auteur institutionnel: UNESCO Santiago | Spain. Ministry of Education La publicación que entregamos contiene algunas de las principales ponencias y reflexiones emanadas de las VII Jornadas de Cooperación Educativa con Iberoamérica sobre Educación Especial e Inclusión Educativa, organizadas por el Ministerio de Educación de España y la Oficina Regional de Educación para América Latina y el Caribe (OREAL C/UNESCO Santiago). Esta publicación tiene a la inclusión en la educación secundaria como tema central, pues constituyó el eje de las VII Jornadas. Es un tema especialmente crítico en nuestra región ya que establece el nivel mínimo necesario para salir de la pobreza, para acceder a un empleo digno y para ejercer la ciudadanía. Sin embargo, el acceso a la educación secundaria todavía es muy bajo en algunos países y es especialmente bajo en el caso de las poblaciones en situación de mayor vulnerabilidad, siendo quienes más requieren acceder a este nivel de estudios para superar su situación de desigualdad.  The 1994 Genocide as Taught in Rwanda’s Classrooms Année de publication: 2017 This blog looks at how textbook and curricula reforms in Rwanda have worked to cover the 1994 Genocide and instill the ideals of tolerance, unity and reconciliation in students. It is part of a series of blogs on this site published to encourage debates around a new GEM Report Policy Paper: Between the Lines, which looks at the content of textbooks and how it reflects some of the key concepts in Target 4.7 in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).by Jean-Damascene Gasanabo, PhD, Director-General, Research and Documentation Center on Genocide, National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG), Kigali, Rwanda. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi saw the slaughter of more than one million people over the span of three months, and placed Rwanda at the forefront of the world’s political consciousness. Almost 23 years later, Rwanda has rebuilt and become a modern hub of progress and development, putting in place social, political and economic systems that are grounded in national unity and reconciliation – with education reforms playing a central role.The large-scale participation of children and adolescents in perpetrating acts of genocide made it clear that an education system that fails to integrate basic human values, will also inevitably fail the nation. Education was used prior to the Genocide to inculcate fear, intolerance and hatred; and so too is it being utilized by the current Government to foster peace and inclusivity, and combat genocide ideology. Post-genocide Rwanda has used education as a main tool to correct biased perceptions of its socio-political history, and to provide accurate representations of the root causes of the genocide, and preventative measures.With over 60% of Rwandans under the age of 24, the formal education system needs to instill the ideals of tolerance, unity and reconciliation in the next generation. With this realization, the Rwanda Education Board and the Ministry of Education have integrated genocide studies in the curricula of its primary, secondary and higher education institutions so that they are better able to lead a nation that is cognizant of its past. Instead of highlighting difference, the national curriculum of post-genocide Rwanda has been reconfigured to emphasize the politics of inclusion and to encourage a spirit of critical thinking that pursues peace, social cohesion and harmony above all else.Prior to the Genocide, educational resources were used as a tool by the genocidal regime to promote ethnic division, discrimination and propaganda. The biased curricula and teaching methods cemented ethnic segregation within classrooms and fostered genocide ideology. The students who were not expelled from primary and secondary school due to the ethnic and regional quota system were forced to identify themselves as being Tutsi – inherently separate to those who were Hutu or Twa. The pre-1994 curriculum lacked “the essentials of human emotion, attitudes, values and skills” as it continued to promote discriminatory and divisive ideologies that were “imparted through formalized rote learning in history, civic education, religious and moral education and languages.”Post-Genocide Rwanda faced the herculean task of rebuilding its dismantled institutions. With a profound lack of qualified teachers, a huge pool of orphaned children, insufficient funds and inaccurate textbooks following the genocide, many education challenges lay ahead. In early 1995, a moratorium was placed on history textbooks which disseminated biased information, as the country grappled with how and to what extent the nation’s past could be incorporated constructively in the education system, without causing pain or resurfacing conflicts.Rwanda chose a gradual, yet comprehensive, approach. In the years immediately following the Genocide, the history curriculum lightly touched on the subject so as to protect students from their recent past, and prevent division in classrooms based on differing family experiences. Classrooms promoted knowledge based on the essential ideas of unity, peace, tolerance and justice. In 2008 the National Curriculum Development Centre within the Ministry of Education published the new history curriculum which incorporated the Genocide against the Tutsi, coinciding with the renewed emphasis on the unifying and inclusive qualities of nationality, citizenship and patriotism, instead of ethnicity.The current national curriculum was formulated by the Rwanda Education Board in conjunction with varying public institutions, UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations. It incorporates the Genocide into the curriculum of every grade level, and discusses it in various contexts suited to the student’s particular stage in learning. Eyewitness accounts and the presence of elders in the classroom allow for a “multi-generational opportunity” for learning. In understanding how violent conflict erupts in society, it is possible to prevent future atrocities from beginning. Teaching the Genocide in present-day Rwanda aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of the event by using primary sources, encouraging class discussions on genocide denial, the persistence of genocide ideology, and the reconciliation efforts embarked on after the Genocide.Moreover, this change in the curriculum has been supplemented by a shift to transform learning from one based on standard rote memorization to one that encourages discussion and a spirit of critical thinking and analysis. This approach identifies the student as an active participant in the learning experience, not merely a silent recipient of history as “evangelical speech.” By promoting an environment that encourages spirited, objective discussions, the Ministry of Education seeks to redress the biases taught by the genocidal regime, as well as prepare young people to thoughtfully and constructively enter the workforce.Genocide education nevertheless faces some challenges ahead. With genocide denial still present, not only are ongoing revisions of educational resources required, but teacher training is also necessary to ensure that revisions to the curriculum are well presented by teachers.The way conflict and genocide has been taught through textbooks in Rwanda has evolved over time. For Rwandans, learning about the 1994 Genocide is not only vital in understanding the history of their country, but also in developing critical thinking skills that help young people become informed citizens in today’s globalized society. Peace education, as well as tools for conflict resolution and genocide prevention, are now heavily featured. Indeed the initiatives embarked on by the education sector signal a promising start to the continuous pursuit of truth through knowledge of the past.In comprehensively integrating the study of genocide into the national curriculum and by empowering students to become agents of their own learning process, Rwanda offers an ambitious recipe for successfully teaching one’s own history for the better.

The 1994 Genocide as Taught in Rwanda’s Classrooms Année de publication: 2017 This blog looks at how textbook and curricula reforms in Rwanda have worked to cover the 1994 Genocide and instill the ideals of tolerance, unity and reconciliation in students. It is part of a series of blogs on this site published to encourage debates around a new GEM Report Policy Paper: Between the Lines, which looks at the content of textbooks and how it reflects some of the key concepts in Target 4.7 in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).by Jean-Damascene Gasanabo, PhD, Director-General, Research and Documentation Center on Genocide, National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG), Kigali, Rwanda. The 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi saw the slaughter of more than one million people over the span of three months, and placed Rwanda at the forefront of the world’s political consciousness. Almost 23 years later, Rwanda has rebuilt and become a modern hub of progress and development, putting in place social, political and economic systems that are grounded in national unity and reconciliation – with education reforms playing a central role.The large-scale participation of children and adolescents in perpetrating acts of genocide made it clear that an education system that fails to integrate basic human values, will also inevitably fail the nation. Education was used prior to the Genocide to inculcate fear, intolerance and hatred; and so too is it being utilized by the current Government to foster peace and inclusivity, and combat genocide ideology. Post-genocide Rwanda has used education as a main tool to correct biased perceptions of its socio-political history, and to provide accurate representations of the root causes of the genocide, and preventative measures.With over 60% of Rwandans under the age of 24, the formal education system needs to instill the ideals of tolerance, unity and reconciliation in the next generation. With this realization, the Rwanda Education Board and the Ministry of Education have integrated genocide studies in the curricula of its primary, secondary and higher education institutions so that they are better able to lead a nation that is cognizant of its past. Instead of highlighting difference, the national curriculum of post-genocide Rwanda has been reconfigured to emphasize the politics of inclusion and to encourage a spirit of critical thinking that pursues peace, social cohesion and harmony above all else.Prior to the Genocide, educational resources were used as a tool by the genocidal regime to promote ethnic division, discrimination and propaganda. The biased curricula and teaching methods cemented ethnic segregation within classrooms and fostered genocide ideology. The students who were not expelled from primary and secondary school due to the ethnic and regional quota system were forced to identify themselves as being Tutsi – inherently separate to those who were Hutu or Twa. The pre-1994 curriculum lacked “the essentials of human emotion, attitudes, values and skills” as it continued to promote discriminatory and divisive ideologies that were “imparted through formalized rote learning in history, civic education, religious and moral education and languages.”Post-Genocide Rwanda faced the herculean task of rebuilding its dismantled institutions. With a profound lack of qualified teachers, a huge pool of orphaned children, insufficient funds and inaccurate textbooks following the genocide, many education challenges lay ahead. In early 1995, a moratorium was placed on history textbooks which disseminated biased information, as the country grappled with how and to what extent the nation’s past could be incorporated constructively in the education system, without causing pain or resurfacing conflicts.Rwanda chose a gradual, yet comprehensive, approach. In the years immediately following the Genocide, the history curriculum lightly touched on the subject so as to protect students from their recent past, and prevent division in classrooms based on differing family experiences. Classrooms promoted knowledge based on the essential ideas of unity, peace, tolerance and justice. In 2008 the National Curriculum Development Centre within the Ministry of Education published the new history curriculum which incorporated the Genocide against the Tutsi, coinciding with the renewed emphasis on the unifying and inclusive qualities of nationality, citizenship and patriotism, instead of ethnicity.The current national curriculum was formulated by the Rwanda Education Board in conjunction with varying public institutions, UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations. It incorporates the Genocide into the curriculum of every grade level, and discusses it in various contexts suited to the student’s particular stage in learning. Eyewitness accounts and the presence of elders in the classroom allow for a “multi-generational opportunity” for learning. In understanding how violent conflict erupts in society, it is possible to prevent future atrocities from beginning. Teaching the Genocide in present-day Rwanda aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of the event by using primary sources, encouraging class discussions on genocide denial, the persistence of genocide ideology, and the reconciliation efforts embarked on after the Genocide.Moreover, this change in the curriculum has been supplemented by a shift to transform learning from one based on standard rote memorization to one that encourages discussion and a spirit of critical thinking and analysis. This approach identifies the student as an active participant in the learning experience, not merely a silent recipient of history as “evangelical speech.” By promoting an environment that encourages spirited, objective discussions, the Ministry of Education seeks to redress the biases taught by the genocidal regime, as well as prepare young people to thoughtfully and constructively enter the workforce.Genocide education nevertheless faces some challenges ahead. With genocide denial still present, not only are ongoing revisions of educational resources required, but teacher training is also necessary to ensure that revisions to the curriculum are well presented by teachers.The way conflict and genocide has been taught through textbooks in Rwanda has evolved over time. For Rwandans, learning about the 1994 Genocide is not only vital in understanding the history of their country, but also in developing critical thinking skills that help young people become informed citizens in today’s globalized society. Peace education, as well as tools for conflict resolution and genocide prevention, are now heavily featured. Indeed the initiatives embarked on by the education sector signal a promising start to the continuous pursuit of truth through knowledge of the past.In comprehensively integrating the study of genocide into the national curriculum and by empowering students to become agents of their own learning process, Rwanda offers an ambitious recipe for successfully teaching one’s own history for the better.  План действий Всемирная программа образования в области прав человека : Первый этап Année de publication: 2006 Auteur institutionnel: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights The Plan of Action for the first phase (2005-2007) of the World Programme was adopted by all United Nations Member States in July 2005. It proposes a concrete strategy and practical guidance for implementing human rights education in primary and secondary schools. On 10 December 2004, the General Assembly of the United Nations proclaimed the World Programme for Human Rights Education (2005-ongoing) to advance the implementation of human rights education programmes in all sectors. Building on the foundations laid during the United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education (1995-2004), this new initiative reflects the international community’s increasing recognition that human rights education produces far-reaching results. By promoting respect for human dignity and equality and participation in democratic decision-making, human rights education contributes to the long-term prevention of abuses and violent conflicts. To help make human rights a reality in every community, the World Programme seeks to promote a common understanding of the basic principles and methodologies of human rights education, to provide a concrete framework for action and to strengthen partnerships and cooperation from the international level down to the grass roots.

План действий Всемирная программа образования в области прав человека : Первый этап Année de publication: 2006 Auteur institutionnel: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights The Plan of Action for the first phase (2005-2007) of the World Programme was adopted by all United Nations Member States in July 2005. It proposes a concrete strategy and practical guidance for implementing human rights education in primary and secondary schools. On 10 December 2004, the General Assembly of the United Nations proclaimed the World Programme for Human Rights Education (2005-ongoing) to advance the implementation of human rights education programmes in all sectors. Building on the foundations laid during the United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education (1995-2004), this new initiative reflects the international community’s increasing recognition that human rights education produces far-reaching results. By promoting respect for human dignity and equality and participation in democratic decision-making, human rights education contributes to the long-term prevention of abuses and violent conflicts. To help make human rights a reality in every community, the World Programme seeks to promote a common understanding of the basic principles and methodologies of human rights education, to provide a concrete framework for action and to strengthen partnerships and cooperation from the international level down to the grass roots.  Die Bedeutung des Holocaust und der Gedenkstättenpädagogik im Unterricht. Ein historisch-pädagogischer Vergleich zwischen Österreich und Bayern In the centre of this research project is a content-oriented comparison based on categories regarding the thematization of the Holocaust in 46 history textbooks for the first stage of secondary education since the beginning of the Second Republic and the new foundation of the Free State of Bavaria in the year of 1945. Based on this thematic constraint, three research questions emerge: 1.How has the representation of the Holocaust in the textbooks changed since the beginning of the Second Republic? What has changed? What has remained the same? 2. What can be deduced from the textbooks concerning the political discourse about the Holocaust? 3. To what extent are the content and the pedagogical-didactical concepts prescribed by the curricula implemented in the textbooks? (By the publisher)

Die Bedeutung des Holocaust und der Gedenkstättenpädagogik im Unterricht. Ein historisch-pädagogischer Vergleich zwischen Österreich und Bayern In the centre of this research project is a content-oriented comparison based on categories regarding the thematization of the Holocaust in 46 history textbooks for the first stage of secondary education since the beginning of the Second Republic and the new foundation of the Free State of Bavaria in the year of 1945. Based on this thematic constraint, three research questions emerge: 1.How has the representation of the Holocaust in the textbooks changed since the beginning of the Second Republic? What has changed? What has remained the same? 2. What can be deduced from the textbooks concerning the political discourse about the Holocaust? 3. To what extent are the content and the pedagogical-didactical concepts prescribed by the curricula implemented in the textbooks? (By the publisher)  Guide de mise en œuvre écoles éducation à l'environnement primaire et secondaire Année de publication: 2005 Auteur institutionnel: China. Ministry of Environmental Protection L'ONU a proposé le développement durable et l'éducation environnementale dans l'Agenda 21 comme un objectif d'éducation pour le XXIe siècle. Dans de nombreux pays développés, l'éducation environnementale est devenue une partie importante de l'éducation qui est compatible avec le développement social. La Chine est également confrontée à de graves problèmes environnementaux qui font plus de demandes pour le mode de développement économique et le niveau de protection de l'environnement. Depuis les années 1980, bien que l'éducation environnementale a été effectuée dans les écoles primaires et secondaires, sa concentration était plus que la transmission des connaissances de l'environnement. Afin de nourrir l'idée de développement durable pour les étudiants et les encourager à prendre des mesures pour un avenir durable, le Ministère de l'éducation de la RPC a officiellement intégré l'éducation environnementale dans le cadre de la fondation des écoles primaires et secondaires. Ce guide vise à fournir des conseils concrets pour les enseignants et autres éducateurs à organiser des activités pour favoriser la compréhension globale du système environnemental des élèves et de développer leurs capacités à prendre des responsabilités pour la protection de l'environnement dans la vie sociale. Il donne également des conseils pour les services administratifs de l'école pour gérer et soutenir ces activités, d'exploiter et de développer de multiples ressources en éducation à l'environnement, et d'appliquer des méthodes et des stratégies pour l'éducation environnementale. En outre, il fournit des méthodes d'évaluation de l'éducation environnementale en tant que point de départ pour ajuster et améliorer la mise en œuvre de l'éducation environnementale.

Guide de mise en œuvre écoles éducation à l'environnement primaire et secondaire Année de publication: 2005 Auteur institutionnel: China. Ministry of Environmental Protection L'ONU a proposé le développement durable et l'éducation environnementale dans l'Agenda 21 comme un objectif d'éducation pour le XXIe siècle. Dans de nombreux pays développés, l'éducation environnementale est devenue une partie importante de l'éducation qui est compatible avec le développement social. La Chine est également confrontée à de graves problèmes environnementaux qui font plus de demandes pour le mode de développement économique et le niveau de protection de l'environnement. Depuis les années 1980, bien que l'éducation environnementale a été effectuée dans les écoles primaires et secondaires, sa concentration était plus que la transmission des connaissances de l'environnement. Afin de nourrir l'idée de développement durable pour les étudiants et les encourager à prendre des mesures pour un avenir durable, le Ministère de l'éducation de la RPC a officiellement intégré l'éducation environnementale dans le cadre de la fondation des écoles primaires et secondaires. Ce guide vise à fournir des conseils concrets pour les enseignants et autres éducateurs à organiser des activités pour favoriser la compréhension globale du système environnemental des élèves et de développer leurs capacités à prendre des responsabilités pour la protection de l'environnement dans la vie sociale. Il donne également des conseils pour les services administratifs de l'école pour gérer et soutenir ces activités, d'exploiter et de développer de multiples ressources en éducation à l'environnement, et d'appliquer des méthodes et des stratégies pour l'éducation environnementale. En outre, il fournit des méthodes d'évaluation de l'éducation environnementale en tant que point de départ pour ajuster et améliorer la mise en œuvre de l'éducation environnementale.  中小学环境教育实施指南 Année de publication: 2005 Auteur institutionnel: China. Ministry of Environmental Protection The UN proposed sustainable development and environmental education in Agenda 21 as an educational goal for the twenty-first century. In many developed countries, environmental education has become an important part of education that is compatible with social development. China is also facing serious environmental problems that make more demands for mode of economic development and level of environment protection. Since the 1980s, although environmental education has been carried out in primary and secondary schools, its concentration was no more than imparting environmental knowledge. In order to nurture the idea of sustainable development for students and encourage them to take action for a sustainable future, the Ministry of Education of PRC has formally incorporated environmental education in the foundation course of primary and secondary schools. This guide aims to provide concrete advice for teachers and other educators to organize activities to foster students’ comprehensive understanding of the environmental system and develop their capacities to take responsibilities for environment protection in social life. It also gives advice for the school’s administrative departments to manage and support these activities, to exploit and develop multiple environmental education resources, and to apply different methods and strategies to environmental education. In addition, it provides methods of evaluating environmental education as a starting point to adjust and improve the implementation of environmental education.

中小学环境教育实施指南 Année de publication: 2005 Auteur institutionnel: China. Ministry of Environmental Protection The UN proposed sustainable development and environmental education in Agenda 21 as an educational goal for the twenty-first century. In many developed countries, environmental education has become an important part of education that is compatible with social development. China is also facing serious environmental problems that make more demands for mode of economic development and level of environment protection. Since the 1980s, although environmental education has been carried out in primary and secondary schools, its concentration was no more than imparting environmental knowledge. In order to nurture the idea of sustainable development for students and encourage them to take action for a sustainable future, the Ministry of Education of PRC has formally incorporated environmental education in the foundation course of primary and secondary schools. This guide aims to provide concrete advice for teachers and other educators to organize activities to foster students’ comprehensive understanding of the environmental system and develop their capacities to take responsibilities for environment protection in social life. It also gives advice for the school’s administrative departments to manage and support these activities, to exploit and develop multiple environmental education resources, and to apply different methods and strategies to environmental education. In addition, it provides methods of evaluating environmental education as a starting point to adjust and improve the implementation of environmental education.  Global school partnerships programme impact evaluation report Année de publication: 2011 Auteur: Juliet Sizmur | Bernadetta Brzyska | Louise Cooper | Jo Morrison | Kathryn Wilkinson | David Kerr Auteur institutionnel: National Foundation for Educational Research The overarching aim of this evaluation is to assess the impact of DFID‟s Global School Partnerships (GSP) programme on levels of global awareness and attitudes to global issues in pupils attending GSP schools in the UK.This main aim can be broken down into four subsidiary aims, namely:1. to measure levels of global awareness and attitudes to global issues amongst pupils taking part in GSP programme activities2. to compare awareness levels and attitudes among pupils in GSP schools with those of pupils in non-GSP schools3. to evaluate whether the impact of GSP on global awareness and attitudes to global issues differs depending on pupils‟ ages and educational stages (e.g. at primary versus secondary level)4. to assess whether levels of awareness and attitudes amongst participating pupils change as the GSP programme becomes more embedded in schools (i.e. whether, over time, the programme has a positive, neutral or negative impact on pupil levels of development awareness).

Global school partnerships programme impact evaluation report Année de publication: 2011 Auteur: Juliet Sizmur | Bernadetta Brzyska | Louise Cooper | Jo Morrison | Kathryn Wilkinson | David Kerr Auteur institutionnel: National Foundation for Educational Research The overarching aim of this evaluation is to assess the impact of DFID‟s Global School Partnerships (GSP) programme on levels of global awareness and attitudes to global issues in pupils attending GSP schools in the UK.This main aim can be broken down into four subsidiary aims, namely:1. to measure levels of global awareness and attitudes to global issues amongst pupils taking part in GSP programme activities2. to compare awareness levels and attitudes among pupils in GSP schools with those of pupils in non-GSP schools3. to evaluate whether the impact of GSP on global awareness and attitudes to global issues differs depending on pupils‟ ages and educational stages (e.g. at primary versus secondary level)4. to assess whether levels of awareness and attitudes amongst participating pupils change as the GSP programme becomes more embedded in schools (i.e. whether, over time, the programme has a positive, neutral or negative impact on pupil levels of development awareness).